It's an Estrogenomenon!

The pendulum has been swinging on estrogen in menopause for a hundred years. It has swung back hard, with a little help from industry friends.

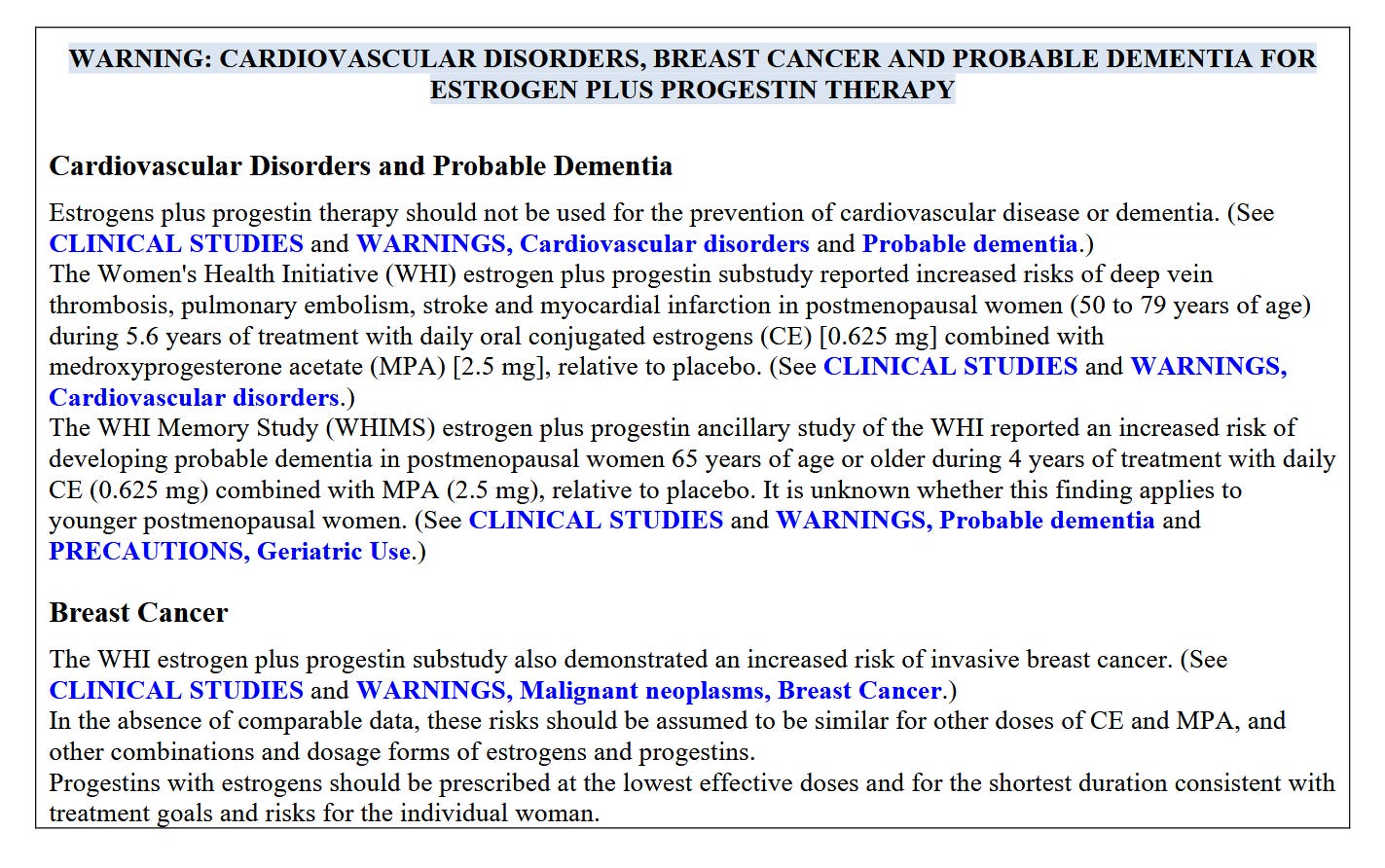

If the algorithm has found you, like it has found me, you know that dozens of online companies are promoting hormone therapy for the symptoms of perimenopause. They’re even selling face creams with estrogen, promising that a few dabs before bedtime will “reverse aging.” And Trump’s remade FDA just rang the bell for a bull market in hormonal menopause products, announcing that the black box warning alerting users to risks of breast cancer, cardiovascular events like stroke and blood clots, and “probable dementia” was all a mistake.

If you have two minutes, you’ll get the gist watching Alicia Jackson, Trump’s appointee to direct the Advanced Research Projects Agency, sum it up at the press conference announcing that the warning label would soon be removed. “Today we have the opportunity to add up to a decade of healthy years to the life of every woman that you love,” she says. And that’s just her opening.

“It’s an American tragedy,” FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, MD, told CBS News. “Fifty to 70 million women over the last 23 years have been denied the incredible, life-changing, lifesaving benefits of hormone replacement therapy because of the dogma.”

A little whiplash with your hotflash? I write about the history, science, and the very online “menoposse” of doctor-influencers pushing estrogen in my latest feature for The Free Press.

Following a century-old pattern of Medicine promoting and then pulling back on estrogen for menopause, this new and mostly-female booster club is promising hormone therapy as the cure-all for everything from wrinkles to Alzheimer’s to divorce. They argue that risks have been overblown, that there’s an optimal “window” in which to begin, and that doctors who try to dissuade patients or refuse to prescribe are causing women to needlessly suffer and age poorly. The ostensible leader of the pack is Texas OB/GYN Mary-Claire Haver, who captures the mood in a comment on Mayim Bialik’s podcast: “We’ve got 96 percent of women raw-dogging menopause.”

Female middle age is certainly having a moment. Melanie Sanders’ hilariously deadpan “We Do Not Care Club” videos struck such a chord they’re being called a “movement.” There are menopause master classes, doulas, conferences, and newly certified clinicians. There’s talk (even if it’s just one TikTokker’s fever dream) of a Perimenopause-a-Palooza with Alanis Morissette headlining.

On the bright side, we’re finally defining our terms: Menopause is marked by the final visit from dear Aunt Flo. But we only know that something’s happened for the last time after it stops happening. Perimenopause is the correct term for the nebulous time span leading up to menopause when the cycle of ovulation, build-up, and release gets glitchy, causing night sweats, day sweats, and if sleep falls victim, a hot mess of fatigue, brain fog, foul mood, etc. As estrogen ultimately wanes, which happens post-menopause after erratic highs and lows, there may be vaginal dryness, pain, recurring UTIs, etc.

Unlike Flo, perimenopause doesn’t bang on the front door. She slips quietly in the back and starts turning on lights you swore you shut off and fucking with the thermostat.

And estrogen is, without question, an effective remedy for these symptoms. Vaginal estrogen, in the form of topical creams, has been shown to have such low absorption in blood levels that it’s safe even for cancer survivors. And it is an evidence-based game-changer in restoring sexual function, preventing urinary tract infections, and boosting quality of life. Physician leaders and medical societies have been asking that the black-box label be removed from topical vaginal estrogen products for more than a decade. If women were scared away from relief by the boldface print (below) on these creams, that is tragic.

Similarly, for the women who were thrust into surgical menopause by a hysterectomy, estrogen supplementation has shown a net benefit for longevity and quality of life.

With these two exceptions, the story on estrogen is much more complicated. Newer products may be safer than old, but promises that they will add years to women’s lives or that starting earlier—and never stopping—is less risky are hardly evidence-based. The bottom line, if you want it now, is that if public health guidance was in need of a correction, we seem to have paraded into a period of overcorrection.

I love digging into complexity and making sense of controversy, and between the reporting I did for The Free Press and another piece on industry influence for The BMJ, I cleared up some of my own confusion, so I’m sharing some takeaways with you here—still free to read and subscribe.

Takeaway #1: The Women’s Health Initiative study was not wrong, but it may no longer be quite right.

The black box warning was added in 2003, prompted by early results from the Women’s Health Initiative, or WHI. One arm of this massive research endeavor by the National Institutes of Health was the largest ever randomized controlled trial of “hormone replacement therapy,” as it was called in the late 90s, when the trial began. More than 27,000 post-menopausal women were split into two groups, one group given placebo and one group given the standard treatment at the time, a combination of conjugated equine estrogen (yes, derived from horses’ urine) and medroxyprogesterone acetate, a synthetic progestin. A subgroup of women who’d lost their uteri took estrogen only.

Formerly “estrogen replacement therapy,” the treatment had evolved into combined estrogen-progestin therapy after it became clear that estrogen alone could cause uterine cancer. The progestins “oppose” the estrogen enough to prevent the lining of the uterus to grow. If the patient has no uterus, progestins are not needed.

Garnet Anderson was the lead statistician for the WHI—I recently reached her by phone and we had a fascinating conversation. As she made clear, the WHI investigators were testing whether HRT prevented heart disease, as the entire medical world believed to be true at the time. “We weren’t questioning the value for treating menopausal symptoms. We were asking, should it be used for even more than that?”

At the time, women post-menopause were routinely offered HRT as a preventive and told they could be on it indefinitely. But as data came in from the study, the investigators weren’t seeing any heart benefit. To the contrary, they were seeing more cardiovascular problems and other issues. The monitoring board let the study go on for a couple years in spite of these early warnings—Anderson told me that every six months, when they submitted data to the overseers, the research team braced themselves for word that the study would be shut down. It finally came when the data showed a clear rise in breast cancer in the group on combined estrogen-progestin—an outcome they wouldn’t have expected to see for many years.

Not only did HRT not prevent heart disease, it was associated with higher rates of breast cancer, stroke, gall bladder disease, incontinence, and dementia. The findings were announced at a show-stopping press conference at the National Press Club. It was an earth-shattering moment in the world of women’s health. Pill bottles were tossed in the trash. Recommendations changed overnight. Prescriptions dwindled in the months following.

One of the menoposse’s criticisms is that the women studied in the WHI were too old—when researchers went back and looked at only the study subjects in their 50s, they have fewer issues. Another talking point, made by Makary as well, is that the breast cancer finding wasn’t statistically significant.

“I will take a little bit of the blame for this,” Anderson told me. Without getting too far into the weeds here, Anderson explained that in the paper that followed the press conference, the table showing the rise in breast cancer was presented with a confidence interval rather than a P-value. But the finding was “highly statistically significant,” Anderson says, (with a P-value of .003 for the researchers in the room).

“This was so significant it made the independent data and safety monitoring board say we have to stop this trial and tell the women.” She went on, “I should have put the P value in the table.” It was her first big paper. “I didn’t realize what kind of a hot potato it was.” Was this early career for you, I asked? Not exactly at age 42, she told me, but it was the first time she was in such a position. Consequently, she added, “I had my first hot flash on the way home from the press conference.”

Anderson acknowledges that maybe the announcement could have been imbued with a tad more nuance. Women who’d had hysterectomies, for whom hormone “replacement” isn’t a euphemism, should have been reassured. And the absolute risks of treatment could have been put in better context—obviously they need to be weighed against the benefits of relief, and a patient’s individual needs and risk tolerance should factor in. Then again, what the media and the medical community at large did with the information was somewhat out of the NIH’s control. And the conventional wisdom for the next two decades was that HRT is too risky. The internet is full of testimonials by women saying they were discouraged, told they were too young for treatment. Which left a gaping niche for telehealth companies to fill.

So the menoposse’s fervor to redeem estrogen is understandable, and they do have some valid points: the WHI studied women who were postmenopausal, not those in the throes of perimenopause. And the drugs it studied—Premarin and Prempro—are no longer the most common. In fact, today’s estrogen patches, gels, and sprays bypass the liver, and studies suggest they are less risky; meanwhile, it’s much easier to access “bioidentical” progesterone, a wholly different molecule than medroxyprogesterone acetate, a progestin that is associated with blood clots and other problems when used for either menopause or birth control.

Lara Briden, a naturopathic doctor in Australia and author of The Hormone Repair Manual, agrees that this is a fair point. A recent paper notes that “a body of emerging clinical and basic research evidence” suggests that progestins are “the principal hormone driving the development and recurrence of breast cancer” and that bioidentical progesterone may be lower risk. “My takeaway from the WHI is that it confirmed that progestins are risky,” Briden told me, though, “that doesn’t vindicate estrogen. The promises are vastly overstated.”

Which brings me to…

Takeaway #2: Progesterone alone works just as well for hot flashes and night sweats

Briden is an acolyte of Jerilynn Prior, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of British Columbia who led randomized controlled trials showing that bioidentical progesterone alone is equally effective as estrogen for treating hot flashes and mood in early to mid perimenopause, without the concomitant risk of uterine cancer. In another timeline, progesterone (which FYI can be purchased in low-dose creams without a prescription) might be the it-drug.

Alas, we are in the estrogen forever—again—timeline. The menoposse is promising the moon, but as there has always been with estrogen promotion, there’s money to follow.

One place to start is the advocacy campaign called “Unboxing Menopause.” Launched in September 2024 by a coalition calling itself the Menopause Advocacy Working Group and its non-profit Let’s Talk Menopause, it was initially focused on getting the boxed warning removed from vaginal estrogen. The FDA exceeded its demands.

Let’s Talk Menopause isn’t transparent with their financials (ProPublica’s database shows it pulled in $800,000 between 2021 and 2023—it will be interesting to see what 2024 looked like) but among the sponsors listed are Bayer, Pfizer, and several telehealth companies that offer hormone therapies.

Adriane Fugh-Berman, MD, is a professor of physiology and pharmacology at Georgetown University and director of Pharmed Out, which monitors industry influence over the practice of medicine. She has been the most outspoken in pointing out these conflicts of interest, countering the messaging that the WHI was “flawed,” that the risks have been overblown, and most absurdly, that “menopause shortens women’s lives,” as Alicia Jackson said at the HHS’s press conference announcing the labeling change. Jackson is also the chief executive of Evernow, a telehealth company selling, what else, menopause therapies.

As an expert witness in litigation against companies that pushed HRT, Fugh-Berman told me she has seen thousands of internal company documents, among them evidence of widespread ghostwriting of medical articles. In one paper, she and colleagues traced dozens of articles authored by physicians who were paid by hormone manufacturers that repeated identical claims about the WHI: that it was “flawed” and “controversial,” and that the women studied were too old or too sick to have benefited from hormone therapy. Pharma “trashed the WHI,” she wrote in a journal commentary. The menoposse seems to be piling on.

Last November, Fugh-Berman joined a group of international researchers and physicians fed up by the hormone-promoting message of the PBS documentary The M Factor, which features many Let’s Talk Menopause-affiliated experts. The group successfully petitioned against the film counting toward continuing medical education credit for physicians, arguing that it contains “nonstop, dangerous disinformation.”

“It’s fine to take menopausal hormone therapy for symptoms,” says Fugh-Berman. “But it should not be used for disease prevention, and it should not be used to treat symptoms that are not associated with menopause. That hasn’t changed.”

If the current administration were truly interested in evidence-based recommendations, we might be initiating another large randomized trial studying current formulations, with an arm looking at progesterone alone. Instead, the FDA opened the floodgates. And in the interest of redeeming estrogen from demonization, influencers seem to have spared no thought for demonizing menopause. (As I write in The FP: Do we really want to return to the trope of menopausal women as disabled, unhinged, and mentally dysfunctional, needing work accommodations and dependent on a lifetime hormone subscription to “feel like themselves again”?)

Hat tip to Briden for pointing to evolutionary biologists for a helpful reframing: human females evolved to thrive with post-fertile levels of sex hormones. Every cell in the body has to recalibrate, and what makes perimenopause annoying—and for some, debilitating—is that estrogen spikes and dips erratically on its way to a more modest stasis. For most, the symptoms recede once we acclimate to the new life phase. That’s an adaptation for longevity.

Update 12/5/25: Listen to this great convo with Ann Marie McQueen of Hotflash Inc. We talk about North America’s obsession with estrogen, why we shouldn’t talk about women of any age as “empty ball sacks,” when doctors act like gods/gurus, and more!

Thanks so much for covering this. The whole topic feels impossibly complicated for me to wrap my head around. I just want simple advice as a perimenopause person. Yes or no? What? How much? I am not bothered by symptoms but if there is a life or health span benefit, I'd like to get it.